Tossing and turning night after night, no matter what she tried, Elspeth Wilson could not sleep. That’s until her partner bought her a teddy bear. Since then, Elspeth has snuggled up to her teddies before drifting away. She speaks to four other neurodivergent and disabled adults whose soft toys are an essential part of their wellbeing, bringing comfort, safety and joy.

I’d always been a good sleeper, until I wasn’t. At the age of 25, insomnia hit.

It was horrible – worse than I could have imagined. Pain. Racing thoughts. A strange energy in my limbs. Never able to get my pillow in a comfy position. I came to dread each night. And each day. The lack of sleep made even simple tasks, like making a cup of tea, seem insurmountable.

I was desperate and tried various things, like getting plenty of fresh air and reading before bed. But they didn’t help.

Until one day, my partner bought me a teddy bear with scruffy fur and a cheeky smile. I named her Clodagh. Teddies were an essential part of my bedtime routine as a child, so it was worth a shot, I thought.

And just like that, I fell asleep.

My childhood teddies were back in my bed. There was Tiger, and a tiny toy version of my dog, Seamus – but it was the soft fur and the huggable size of Clodagh that allowed me to sleep restfully when that felt otherwise impossible.

I sleep with my teddies every night if I’m at home. They provide snuggles, softness and something to hold, no matter what else has been going on in my life.

In many cultures, including British culture, we accept young children with teddies as cute and natural. We recognise the urge to have something that is ours, that we can draw comfort from, that we can snuggle up to when we need to be soothed. But there comes an age when expressing those needs in a visible way by relying on an inanimate object – like a cuddly toy – becomes at best, pitied, at worst, despised.

As we grow up, society tells us we should stop externalising our needs as obviously as when we were babies or toddlers. In Britain, it’s taboo to scream or break down crying in public – unless we’re in situations where that’s acceptable, like funerals.

As a teenage girl, I read the messages from society loud and clear: don’t take up too much space, be accommodating, be pretty, don’t complain. When older men harassed me, I felt like I had to put up with it. Those outward displays of emotional distress I had as a child simply weren’t accepted any more.

I internalised a lot of my pain, tucked it into corners I thought were hidden – something made even more challenging by undiagnosed autism. I was ‘masking’ my real self to fit into a neurotypical world.

Years later, these supressed feelings came out in a period of reckoning through panic attacks, disassociation and feelings of paranoia. Squashing down feelings doesn’t mean they go away – it only delays and reshapes the problem.

During this time, I was struggling. I was traumatised and I felt alone and isolated – partly because I had never learned a language in which to talk about my problems and things that had happened to me.

Elspeth and Clodagh.

The safety of my teddies

My teddies taught me it’s not only people that can care for you. When I think about it, it seems obvious – we already have so many machines and other objects involved in our care, like duvets, ovens and washing machines. But it took me a while to realise what a crucial part soft toys were playing in my healing.

My soft toys soothed a lot of the worst symptoms of my PTSD; holding and cuddling them helped with insomnia, nightmares and tummy aches. When I felt overwhelming nausea, I would place Clodagh on my stomach. It would partially replace that sensation with a sense of comfort.

I turned to my teddies at a time where I needed physical touch in a way that was safe and in my control.

I wasn’t in a place where I could handle the responsibility or the cost of a pet, and I was frightened of intimacy with other people. My teddies lent a softness to my life that felt out of reach, as I introduced hard boundaries with other people to protect myself. And they didn’t ask for anything back.

There’s a lot more research on the health benefits of soft toys to children – particularly neurodivergent and disabled children – than there is on their benefit to adults.

This research makes clear that soft toys can help children through traumatic situations, communication difficulties and sensory overwhelm. But I knew from my own personal experience that all this applied to my adult self too – after all, are our needs for safety and comfort really so different from our childhood selves, or are they just repressed?

Conversations in mainstream media about adults with soft toys are often about collectors. But on forums and blogs, people have shared their experiences of “trauma teddies”, using a soft toy to stim (a repetitive motion that can be soothing, particularly for autistic people), or buying a soft toy to help them sleep and feel less alone after a bereavement. Such stories were instantly relatable.

Speaking to other disabled and neurodivergent people, I learned many of us have strong attachments to teddies and other soft toys. And as these conversations with Jess, Quinn, Emily and Rita (not her real name) prove, there are many ways they support our health.

In search of stability

Pierre is a fuzzy brown bear. He was bought for Jess by her mum on a family holiday in France when she was four years old – Jess was distraught because she’d left her comfort blanket behind. She wanted her new teddy to have a French name, so he would know she was talking to him, so her mum suggested Pierre.

Twenty-six years later, Pierre remains a constant in Jess’s life. “He’s the best. He’s super-stable. He’s been with me through everything,” she tells me.

Jess has colitis, and Pierre has been by her side in the times she’s found it difficult to maintain other relationships. Jess’s condition can be isolating, and she’s had struggles with her mental health along the way, meaning that sometimes she can’t be as active or as social as she would like. Not everyone understands that. “You lose people along the way,” she explains.

Jess and Pierre.

When Jess goes hospital, Pierre is there too. “Sometimes people have brought him in without me even asking. When my mum was alive, she would bring him,” she says. It’s beautiful to me that people in Jess’s life understand the connection she has with Pierre. They know that he will support her in a time of recovery.

Jess and I have both found that our teddy bears combat the loneliness that disabled people can face as a result of stigma, lack of understanding and lack of support to maintain our social lives.

For almost three decades, Pierre has provided Jess with stability and company in an often difficult, ableist world.

It’s clear from Jess’s smile and the fondness in her voice that Pierre has been there for her through all kinds of ups and downs: bereavements, flare-ups of her illness, new relationships and the launch of her own business. “He’s always out and proud. He’s just part of me,” she says.

Reconnecting with our bodies

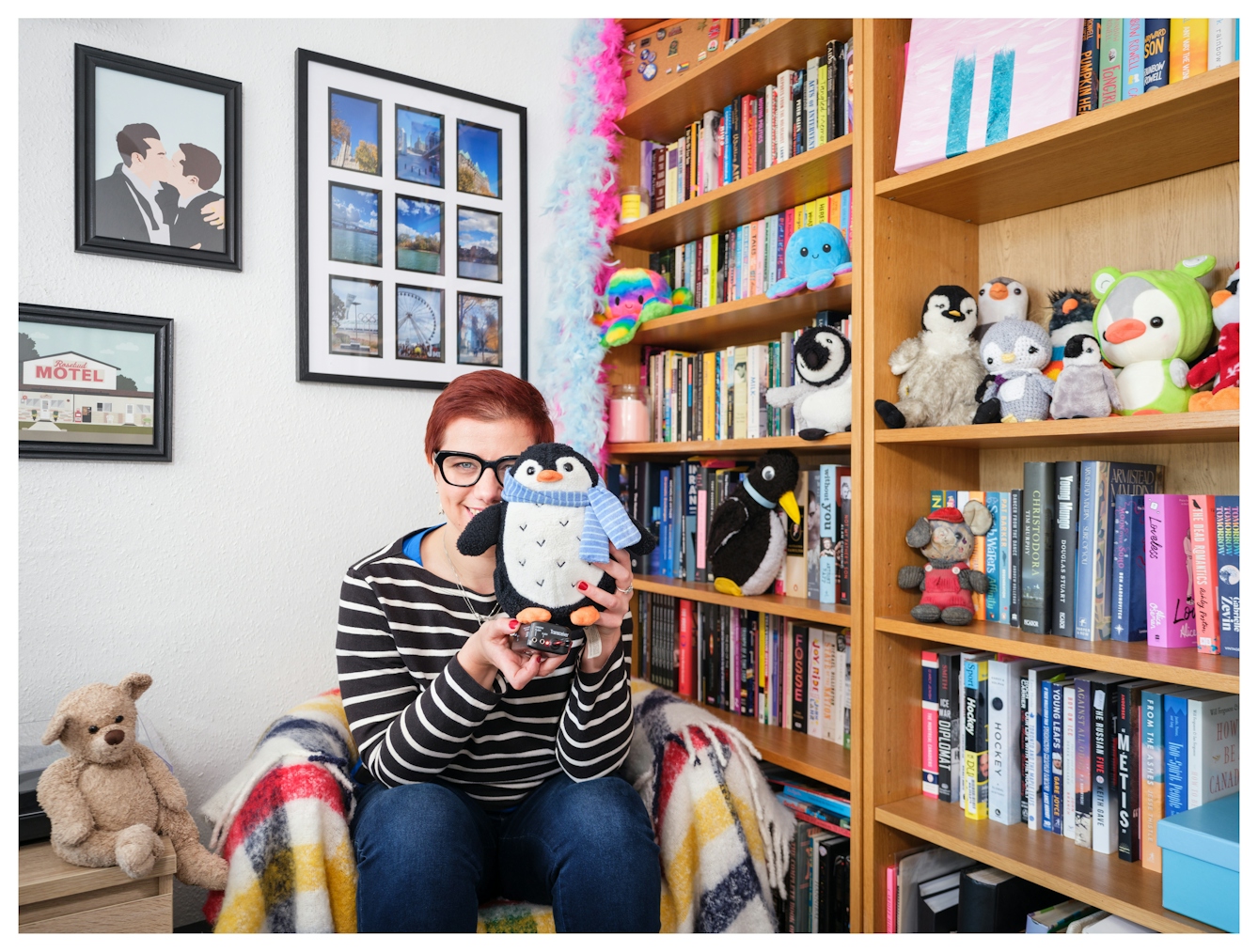

Quinn knows just how important soft toys can be for healing. They talk me through their collection of over 60 soft toys of different shapes, colours and sizes. Many of these are characters from games and media that Quinn loves, particularly horror. They also have a collection of vintage Nosy bears from the 1980s.

These soft toys are expressions of Quinn’s joys and interests. But they also play a crucial role when Quinn has a dissociative episode.

When experiencing dissociation, Quinn can feel like the world around them isn’t real or they aren’t real. They find that to recover from these kinds of episodes, it’s necessary to ground themself back in reality. Soft toys are a great way of doing this because they’re so tactile.

It’s clear all of us experience our soft toys as a ‘someone’ that we can spend time with and who makes us feel less alone.

Quinn utilises the very physical nature of soft toys. They have a gigantic octopus plushie that’s great when they’re feeling anxious. It’s almost bigger than they are, so they can give it a good squeeze.

“Small toys with big personalities are fantastic because then you can start acting out some ridiculous kind of scenario and it just rockets you back into ‘oh, things are actually okay even if I feel terrible’,” Quinn tells me.

The huge differences in size and texture of soft toys means that they can meet so many different needs, sensory and otherwise. I can relate. My tiny teddy, Mills, comes with me on trips where it’s just not practical to bring a bigger bear.

I can’t get quite the same comfort from holding Mills because they’re so small. But even knowing they’re with me and that I can stroke their fur can be soothing in a new environment or when travelling – both things I find anxiety-inducing.

Quinn and Twinkle, Surprise, Snowplay, Popper, Gumlet and FlyBye.

Rita, a 54-year-old writer and mental health professional, also uses her soft toy to reconnect with her body. She has been sleeping with a hot-water bottle in her bed for seven years. This began when a counsellor she saw after her dad died advised her to always sleep with something warm. Two years ago, when Rita's mum died, she bought herself a long hot-water bottle with a furry cover and a face in the shape of a sloth. She’s slept with him ever since.

Rita wonders whether there’s an “unconscious resonance” in returning to having a soft toy as an adult after a parent dies. “Cos you never stop being a child, no matter how old you are,” she says.

And as with my own experience, Rita's relationship with her cuddly now extends beyond sleep, particularly after she had two head injuries last year. Having her sloth in her bed helped her feel less alone. As with Jess, he was there for her during a time of poor health when she would have otherwise been isolated.

Closeness and connection

It’s clear all of us experience our soft toys as a ‘someone’ that we can spend time with and who makes us feel less alone. But they also facilitate relationships with other people, and that’s another way they help us feel less isolated.

Quinn and their partner put on different voices for their soft toys, using them to soothe and entertain one another. And Jess feels able to relate to people when talking to them about her soft toys. “It just gives you that closeness with someone else. If you feel that connection with a soft toy, you understand the love that’s there,” she says.

In 2022, I was followed on Twitter by an account called Sad Penguin Time. It details the life of Tim the penguin, with a focus on how he’s feeling day to day. It turns out that the human behind the penguin is Emily, a 38-year-old writer and project manager from Cardiff.

For Emily, the account has become a way for her to vent and talk about mental health through a penguin who isn’t necessarily attached to her name. It provides her a slight sense of detachment when she talks about difficult feelings or experiences through Tim.

It’s also been a point of connection with several of her friends, who engage with Sad Penguin Time. “Even though they know it’s me. I think for neurodiverse friends it’s a good way of going, yeah, I feel like the penguin today. He’s taken on a bit of a personality.”

Emily talks about how, as someone who is autistic and has ADHD, connections over soft toys can provide a safe space with other neurodivergent people. As she puts it, it’s about being able to “bounce off another person who might not have the exact same experiences but would get where you’re coming from, which we don’t get very often”.

Emily also mentions the funny side of Tim, describing him as a “comedy penguin” with a “stupid little face”. She is often amused by his antics, like when he looked as if he was going through an existential crisis.

Rita and her sloth.

Although soft toys can support people through the most isolating, traumatic events, there’s a lightness to them too, which is a part of their beauty. They can be fluffy, squishy, have silly faces, make silly noises, be funny.

Rita says there’s “so much humour” with her sloth. When she has an audience, she palpates his belly when it’s full of water so it looks like he’s breathing, and that provides a point of laughter to connect with friends. “I guess that’s what’s really supported my mental health over the years,” she tells me.

A source of creativity

The comfort and care of soft toys extends beyond the necessity for survival and into the realm of joy, happiness and play – something that feels hugely important to hold on to and celebrate in a world where adult fun is often organised and limited in terms of what is socially sanctioned.

Neurodivergent people in particular have historically been stigmatised as lacking in empathy and imagination. But, in fact, they are very often the opposite.

Our soft toys are often part of a rich world of vivid imagination and connection. There’s inventiveness and empathy through storytelling and performance.

For Emily, soft toys have so many creative, sensory elements. “Surely that’s something you want to embrace and have fun with,” she says.

Emily points out that this creativity might be frowned upon in a way that something like puppetry wouldn’t be because it’s elevated as an ‘artform’, whereas soft toys are seen as personal and ‘childish’. But for me, I can’t pinpoint or divide where my creativity starts and ends – it’s as much in my relationship with my teddy bear as in my poetry.

As Quinn says, “We’re cool because we can see these little bundles of fluff and fabric and project entire personalities on to them and create these wonderful stories and achieve great comfort from them. That’s awesome. How incredible is that?”

Quinn feels that being neurodivergent means we get “less opportunity” to connect with ourselves “authentically”. But they believe that when we are telling stories with our soft toys, we are also telling stories to and about ourselves.

This type of play can provide a means of escape from an ableist world, and can help us make sense of difficult things – such as when Quinn spent a lot of time talking to their soft toys during lockdown.

Telling ourselves and others these stories is hugely important in a world which doesn’t value our narratives, where we have to constantly reclaim our self-worth and self-esteem.

Emily and Tim.

Proudly celebrating our teddies and toys

There’s still a wider sense among the people I talk to that soft toys are derided and not taken seriously in terms of potential health benefits. I was even worried no one would want to be interviewed for this piece or willing to talk publicly about how their soft toy supports their health.

Rita says that in her past career as a social worker, soft toys never came up as something that could help people. But she hopes that, in the future, she and other people working in mental health will use soft toys as a therapeutic offering.

Speaking to Emily, Rita, Jess and Quinn allowed me to reflect on my relationship with my teddies with pride. Pride at my persistent survival, pride at my desire to seek care and comfort in a world which doesn’t prioritise it, pride at my imagination, pride at my authenticity.

Being able to own and celebrate our relationships with soft toys is crucial to heightening the benefits we get from them in the first place. After all, shame and secrecy are things disabled and neurodivergent people are often forced to live with. Learning to be unashamed about our soft toys is one way we can combat this.

Quinn had spent time reflecting on how we can give ourselves (and others) permission to find joy in soft toys and elsewhere. Initially, they were “overcome” with “shame” and “self-conflict” when they thought about discussing their soft toys. They weren’t sure they were ready to be open about that part of themselves. But then they realised their soft toys have helped them survive periods of dissociation, explore their interests and enjoy happy times with their partner – all things to celebrate.

“I am proud of anyone who has gone through so much pain but knows how to take care of themselves in this way,” Quinn says. They encourage people to keep enjoying their soft toys, regardless of what other people might think.

For neurodivergent and disabled people, proudly claiming our interests and ways of coping with the world can be enormously liberating in a society which wants us to minimise and mask ourselves. Soft toys can be a route to accepting ourselves against the odds.

Soft toys soothe minds and bodies in many and varied ways. My journey with my teddy bears as an adult started as one of urgent need and has expanded into one of recovery and connection with other neurodivergent and disabled people. These soft toys provided immediate sensory support and originally helped me with insomnia, and they have since provided me with a sense of community, solidarity and (self-) exploration.

These are often lifelong relationships that change, grow and expand over time, providing stability in the face of fluctuating health and big life changes. Quinn points out that “there’s nothing wrong with finding joy in the things that are bright and soft and colourful”.

Soft toys provide moments of joy and glimpses of what society could be like if we looked at health more holistically, prioritising support, care and comfort for adults in inventive ways.

I feel so much calmer, happier and able to cope with my life now, and my teddies helped start me on this process of recovery.

I still sleep with my teddies every night and I don’t see that changing. They help my health through the good times as well as the bad. They’re a part of me – touching on the areas of myself that are the most maligned and stigmatised, and helping to bring them up to the light.

About the portraits

Each of the participants in this story created their own portraits though an assisted self-portrait. This collaborative approach to making portraits, created by the socially engaged practitioner Anthony Luvera, aims to redress the conventional imbalance of power between the photographer and the photographed.

Throughout the process the participants chose where and how their portrait would be made and, using a remote trigger, they were in control of the moment the image was captured. During the shoot each participant could review their images in real time on a screen and evolve their portrait following their own creative instincts. After viewing the complete set of images, each participant chose the portrait that they felt represented them best.

The role of the photographer in this process was one of technical assistant and creative support.

About the contributors

Elspeth Wilson

Elspeth Wilson is a writer and poet who is interested in exploring the limitations and possibilities of the body through writing, as well as writing about joy and happiness from a marginalised perspective. Her debut poetry pamphlet, ‘Too Hot to Sleep’, was published by Bent Key Publishing in April 2023. Her creative work on embodiment and accessibility has been supported by Creative Scotland, Arts Council England and the Royal Society of Literature.

the participants

Elspeth, Jess, Quinn, Rita and Emily each devised, created and captured their own portrait.

Benjamin Gilbert

Ben is a senior photographer for Wellcome. He is happiest when telling stories with his photographs, whether that be the health implications of rural-to-urban migration in India, or the dedication of the workers who power the NHS.