When the daughter of 18th-century industrialist Matthew Boulton lost an incisor, her wealthy father turned to the latest treatment to save her smile – a tooth transplant using a live donor. But in her very anonymity, the girl who sold her tooth manages to tell a story about capitalism, class and the price of beauty.

In the late 18th century, a teenager from London lost one of her teeth in an unusual way: the rich and famous Birmingham industrialist Matthew Boulton bought it. He hired a dentist to prise it from her mouth and implant it into his daughter.

After the transplant, the girl was left a guinea richer and an incisor poorer. But this, recorded in a letter from Boulton to his son, is all we know about her.

As a historian of medicine I’ve written a lot about tooth transplants, which has involved reading my fair share of correspondence. I’m used to both partial records and biased accounts. And, having read a lot of Boulton’s other letters in various books, there’s something ugly about what he left out of this one. Without bothering to record the girl’s name, Boulton must have decided she was nothing but a body, uncomplicatedly for sale.

In my profession I’ve written extensively on transplant surgery but not very much about social class. As someone from a working-class background, however, it’s upsetting to come across someone who could have been your ancestor depicted as nothing but the grower of a tooth.

But where do you start telling the story of a girl without a name? How do you acknowledge the humanity of someone without a story? In this case, we must start with the Boultons. The unnamed girl only appears in historical records, after all, because a rich man wanted his daughter to marry well.

Eighteenth-century beauty expectations

It was early summer 1787, and Matthew Boulton’s daughter, Anne, felt an excruciating pain electrify her skull. She pleaded with him to make it stop. Anne was 19, and her sweet tooth was already responsible for several missing molars.

Matthew was starting to despair. The 18th century generally revelled in shallow, external beauty ideals. False legs became shapely, and spectacles started to connote intelligence (not just a sign of poor vision).

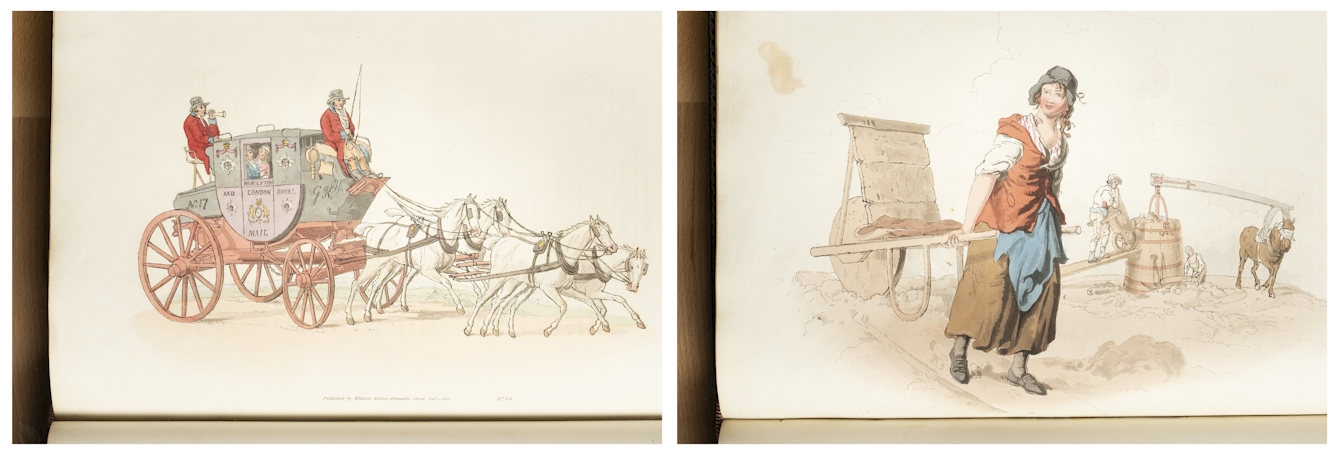

“The clanging of milk pails, the dustman’s wooden rattles, and street-hawker melodies eventually gave way to gentler Mayfair.”

Dentists were some of the most vocal supporters of a new market in beauty. Nicholas Dubois de Chémant compared the eyes to the teeth – the eyes were the window of the soul, and the teeth the index of health. James Bladen Ruspini warned of “the foetid smell arising from carious Teeth and diseased Gums”. And “no excuse can be made or taken”, wrote Oxford operator for the teeth Mayer Lewis, “for a dirty and foul set of teeth”. Should you want to be a social success, or rise in the social ranks, you simply had to look after your teeth.

With each twist of the dentist’s key, then, and each anguished cry, Matthew Boulton felt his daughter’s marriage prospects recede. Given the immense pressure on young women to look their best, the possibility of losing yet another tooth – this time an incisor, right in the middle of her smile – might spell disaster.

Should you want to be a social success, or rise in the social ranks, you simply had to look after your teeth.

Would his beloved “fair maid of the mill” ever find a husband? She was, after all, already at a disadvantage, he thought, thanks to a diagnosis of club foot.

But there was hope. For years, Boulton had been nobbling royalty and hanging around court. He’d been trying to flog all manner of opulence, from silver wine coolers to ormolu-mounted Blue John perfume burners.

While socialising in his rarefied circles, he’d befriended a man called Charles Dumergue, dentist to the royal family. And when ‘Papa Boulton’ and ‘Daddy Dumergue’ (as they called one another) exchanged letters on the subject of Anne’s toothache, they decided father and daughter should head to London for one of the era’s most popular beauty treatments: a tooth transplant.

Several days later, Anne’s carriage clattered past farm and field, and into the city. The clanging of milk pails, the dustman’s wooden rattles, and street-hawker melodies eventually gave way to gentler Mayfair, and the carriage rolled up to Dumergue’s well-appointed surgery.

The human cost of saving a smile

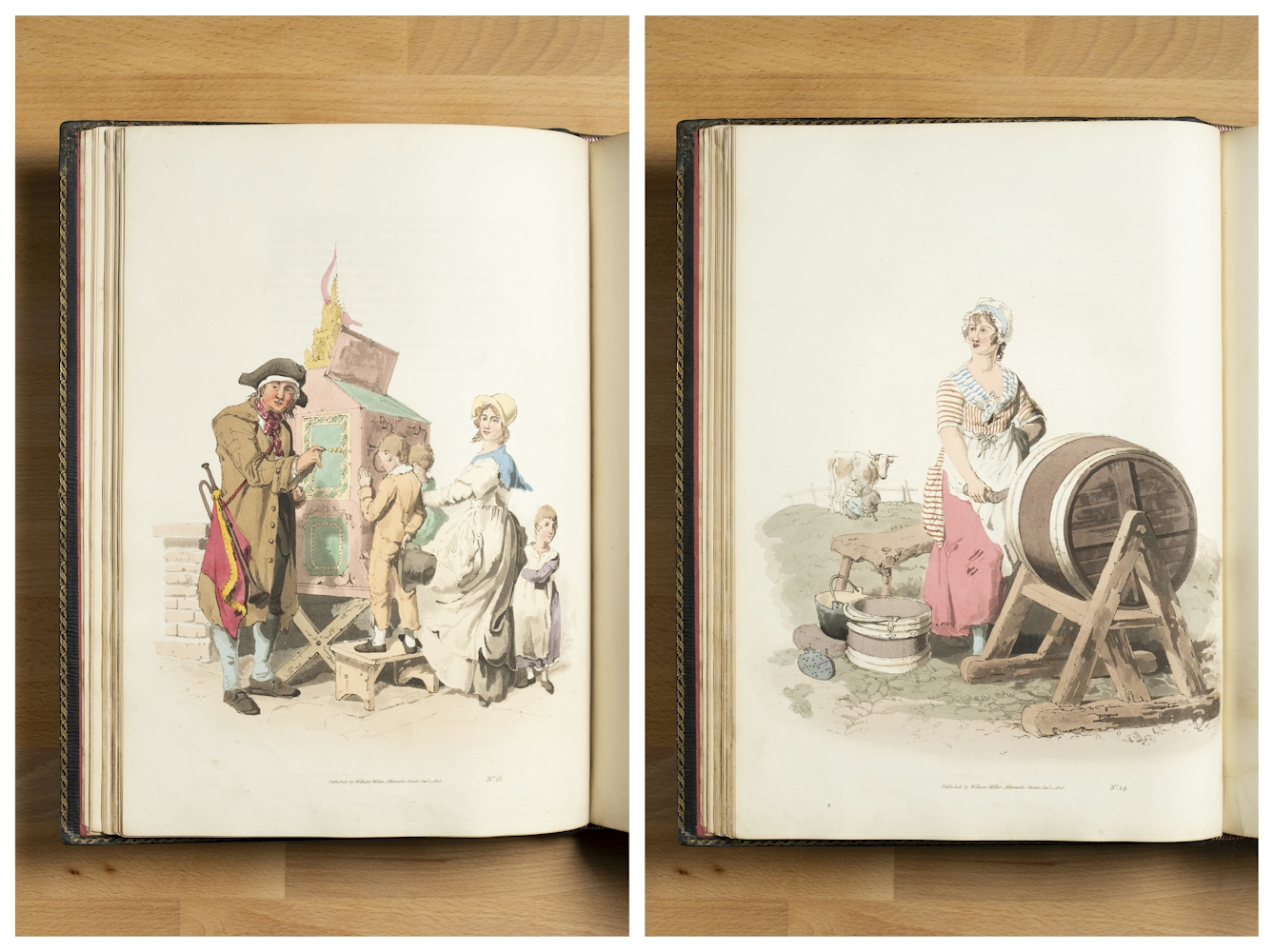

In 1787, tooth transplants were so popular that the satirist Thomas Rowlandson depicted one. His cartoon shows the Italian dentist Bartholomew Ruspini – father of James Bladen Ruspini, mentioned above – operating. And it gives us an idea of the scene that the Boultons would have been presented with when they arrived at Daddy Dumergue’s surgery. The fate of this anonymous girl’s tooth was clear: to enhance Anne’s chances on the marriage market.

Boulton’s letters continue, telling his and Anne’s story well after the shameful tooth transplant. On their way home, for instance, they stopped off in Slough to call on the astronomer William Herschel, to see his new 40-foot telescope. It was the end of June. By October, Anne wanted a horse, which fetched a price of £25 – many times more than what Boulton spent purchasing a part of someone else’s daughter.

“Working-class people were seen as farm animals, breeding indiscriminately, lacking morals.”

But the person I really want to check up on has disappeared from the records without a trace. She would have made her miserable way out of the surgery and back to anonymity.

Rowlandson knew, like other commentators at the time, that transplants were iniquitous, and he dedicates a good proportion of his canvas to the children whose mouths had effectively been robbed. I, too, have a desire to rail against her anonymisation.

But it’s very hard to tell stories about the people populating the working classes (or “the lower orders”, to use the 18th-century term). Partly this is because most people tend not to leave any kind of deliberate or articulate record of themselves. But in the absence of such records, can we respect the individual by taking time to acknowledge how ‘individuality’ applied only to those of a certain social station?

Certainly, thanks to economists like Thomas Malthus, working-class people were seen as farm animals, breeding indiscriminately, lacking morals. It was the same philosophy that underpinned the notoriously dehumanising Victorian workhouses.

The 18th-century tooth transplant, too, embodies this distinction between the individuals with money, and the veritable cattle without, reduced to the level of a resource to be consumed and disposed of.

It’s hard to say what Anne and her father personally felt about raiding a teenager’s mouth. There’s evidence to suggest that Boulton had a conscience. He’s now celebrated for taking a stance against slavery, and famously looked after his own workers into their old age. But in their vast correspondence, none of the Boulton family seem to have given the girl a second thought.

Perhaps he was ashamed. Literature and satire from the period, after all, screamed about the iniquity of tooth transplants.

“I would rather beg in the streets,” said the pawnbroker in Helenus Scott’s ‘The Adventures of a Rupee’, “than ride in a coach by means such as these.” And to have a figure like a pawnbroker utter these lines gives the statement great moral force: trading body parts is low, even for someone who makes their living from human misery.

By the end of the century, cases of wealthy recipients dying of infections started to come to light. Thanks, also, to the advent of new porcelain dentures, tooth transplants more or less fizzled out.

The irony of the tooth-transplant boom is that they supposedly scientifically proved that all bodies are equal in a fundamental way. At least, in principle. Yet transplants became popular because the vast inequalities of an unregulated capitalist state – a society that created property of children’s bodies. And, in a world still defined by sharp class division, it’s worth remembering that the operation only came to an end when it was no longer the best option for the aspiring middle classes.

About the author

Paul Craddock

Paul Craddock is a cultural historian and author of the award-winning book ‘Spare Parts: A Surprising History of Transplants’. He speaks regularly on the history of medicine, trust in science, and working-class contributions to science and medicine. Paul is a Science Museum Group Senior Research Associate, an Honorary Professor in History of Surgery and Society at UCL, and a Visiting Lecturer at Imperial College London.