It's 15 years since England's last public post-mortem, but what was the history of human dissection up to that point?

Before the invention of X-ray in 1895 there was really only one way to accurately study the human body, and that was to cut it open. The first public dissection was performed by the Greek physician Herophilus in the early third century BC. Since then dissection has had a turbulent history. Many religions believed opening up the earthly body could cause pollution, damage the soul, or even mean loss of the afterlife. Because of this, dissection (and therefore anatomical medicine) didn’t progress much until the 13th century when Frederick II issued a decree allowing it for anatomical study. Even then available bodies were limited. People were perhaps understandably reluctant to hand over their dead relatives.

While anatomy stagnated, the beliefs of the Greek physician Galen about the human body dominated, despite most of his work being on macaques. When the anatomist Andreas Vesalius began dissecting bodies in the early 16th century, he quickly noticed a discrepancy between what was written by Galen and what he could see in front of him. Some people found Vesalius’ challenge to Galen’s accepted ideas shocking, but others were inspired to take up the scalpel themselves. By the 18th century nearly every medical school in Europe had its own anatomy theatre, and many dissections were public events.

In pictures

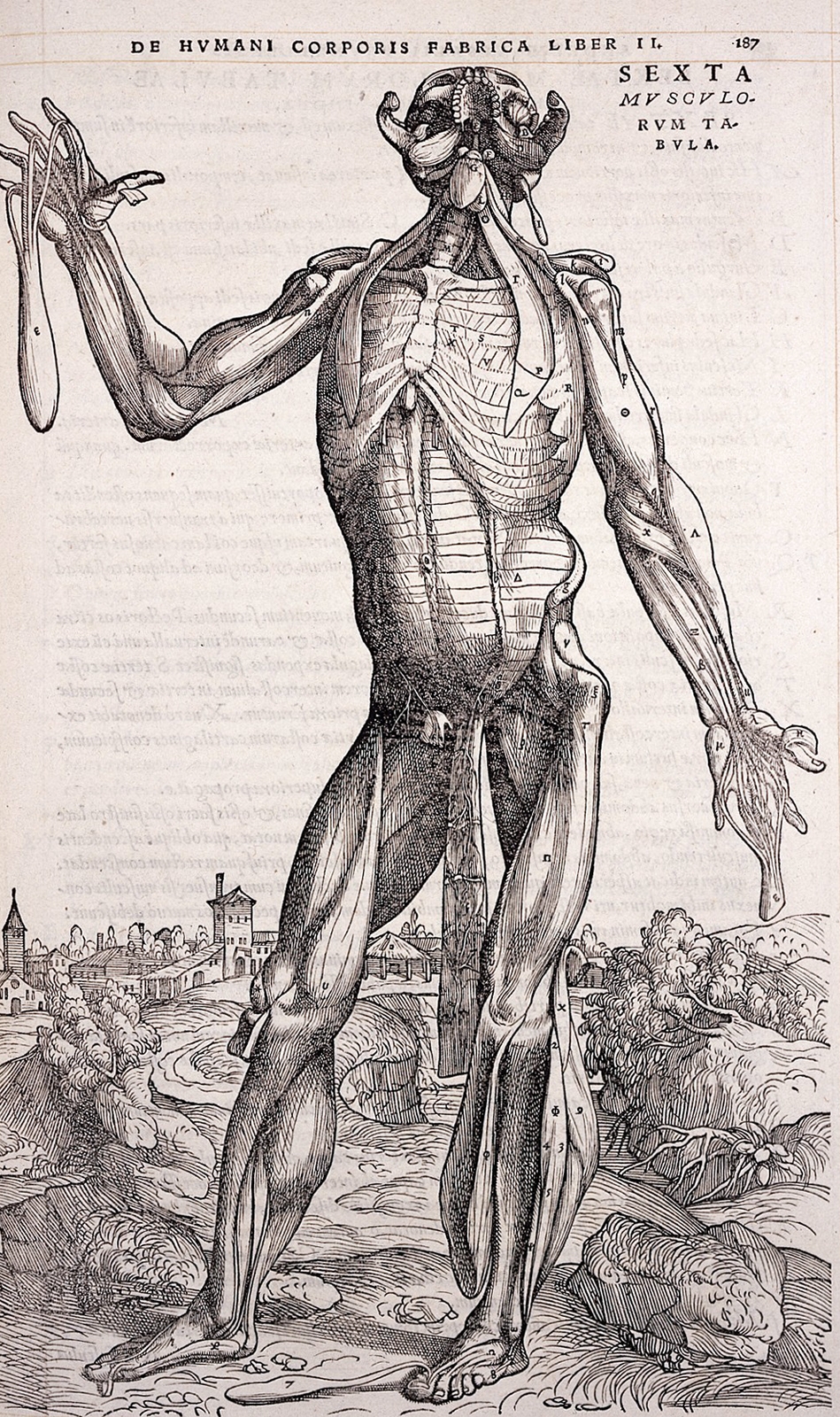

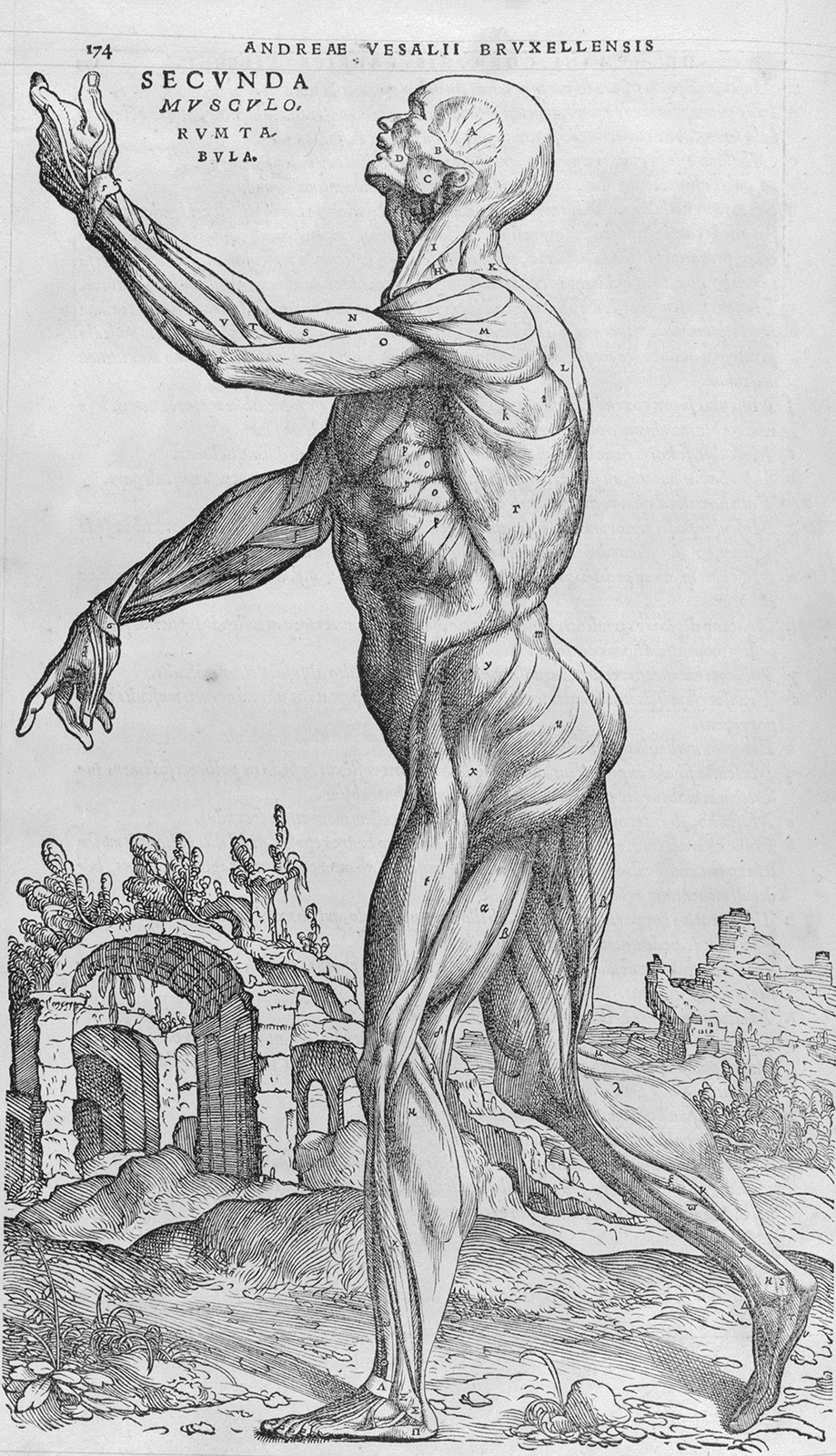

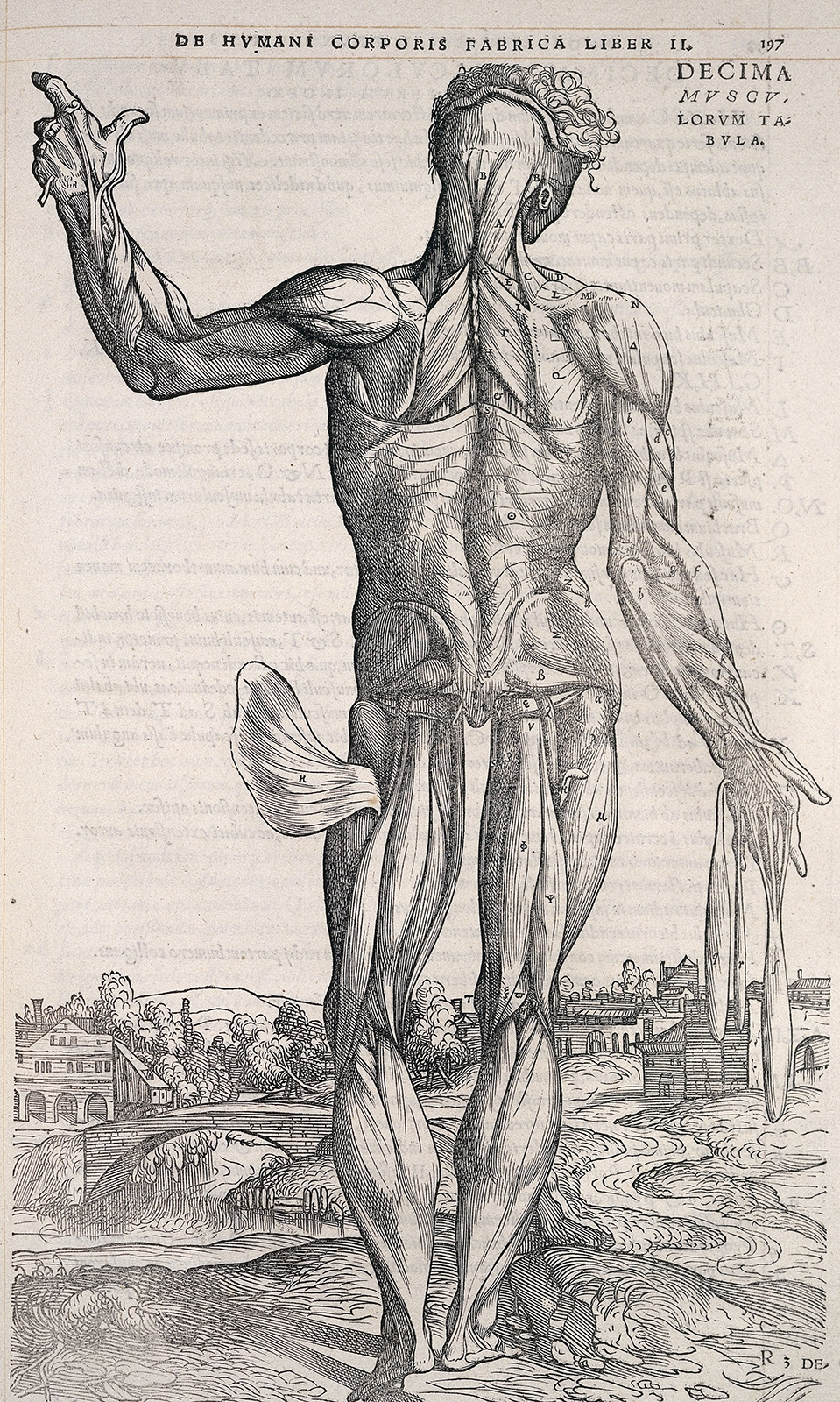

A page from 'De humani corporis fabrica' by Andreas Vesalius, published in 1534.

A page from 'De humani corporis fabrica' by Andreas Vesalius, published in 1534.

A page from 'De humani corporis fabrica' by Andreas Vesalius, published in 1534.

Despite the growing popularity of dissection in Europe, it remained illegal in Britain until 1565 when pressure from medical schools and students forced a change, allowing specific groups of physicians and surgeons some limited rights to dissect cadavers. Later, in 1751, the Murder Act worked as both a deterrent for murder, and a way to provide bodies for study. It allowed that any person executed for murder could also be sentenced to a public dissection once they were dead. This was often feared more than the execution itself, as it would be difficult to answer the call on Judgement Day if your organs were in a jar and your boiled bones boxed in a drawer. After your dissection you could then suffer the further indignity of your skin being made into money purses, calling cards and snuff boxes to sell to the eager public.

Even if you were a lawful person who received a Christian burial you were still at the mercy of body snatchers. It was difficult to get hold of human cadavers legally, and so body snatching was a growing industry in the 18th and 19th century, not least because it was possible to earn up to £10 per body. Although there were things you could do to protect your body after death, they weren’t always successful. Charles Byrne, famous for being 8 ft 4, feared falling into the hands of surgeons after death, so paid to be interred in a lead coffin and dropped in the ocean. Unfortunately the only thing that sank was the empty coffin, as the body of Charles was already on its way to the residence of the distinguished 18th century surgeon, John Hunter.

In pictures

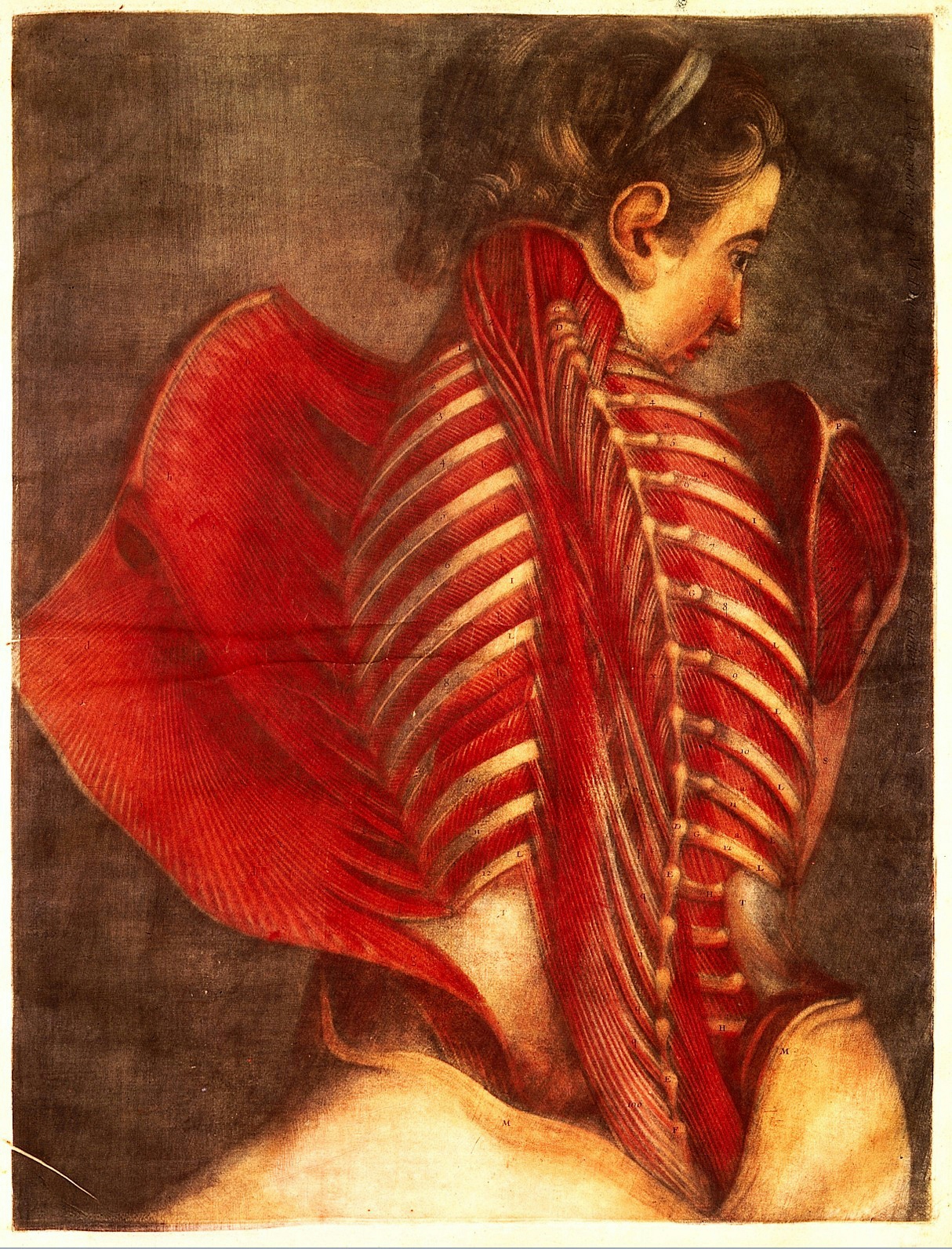

This mezzotint by Jacques-Fabien Gautier Dagoty shows the muscles in a woman's back.

This Dagoty mezzotint shows two dissected male figures, one seated, the other standing behind, with viscera on the floor in the foreground.

More muscles by Dagoty.

A source of entertainment and ephemera, anatomy was also an inspiration for artists. The painter Jacques-Fabien Gautier Dagoty created some stunning depictions of dissections in the late 18th century, using a revolutionary form of colour printing that allowed multiple prints to be made of the circulatory, musculatory, and reproductive systems. Gautier initially worked with an anatomist to create his images, but later claimed to conduct his own dissections. The women portrayed in his images are all classically beautiful, often with intact shoulders and breasts exposed, and Gautier has been accused of intending his images to be titillating. At the time social conventions wouldn’t allow a doctor to gaze upon a naked female body, so most of their knowledge was gained from examining dead female bodies on the dissection table. Young women in their reproductive years were particularly prized for study.

In pictures

This image shows a wood and ivory model loosely based on the 1632 painting 'The Anatomy Lesson of De Nicolaas Tulp' by Rembrant van Rijn. Nicolaas Tulp (1593-1674) was a Dutch anatomist. In the model and painting he is shown lecturing to an audience while dissecting a female corpse.

Edward Jenner (1749-1823) was a pioneer of vaccination, but he was also known for his delicate dissections. Here a section of stomach has been flattened and injected with wax to show the veins and arteries, as well as the delicate membrane of the stomach wall. It may have been used as a teaching aid to show the structure of the stomach.

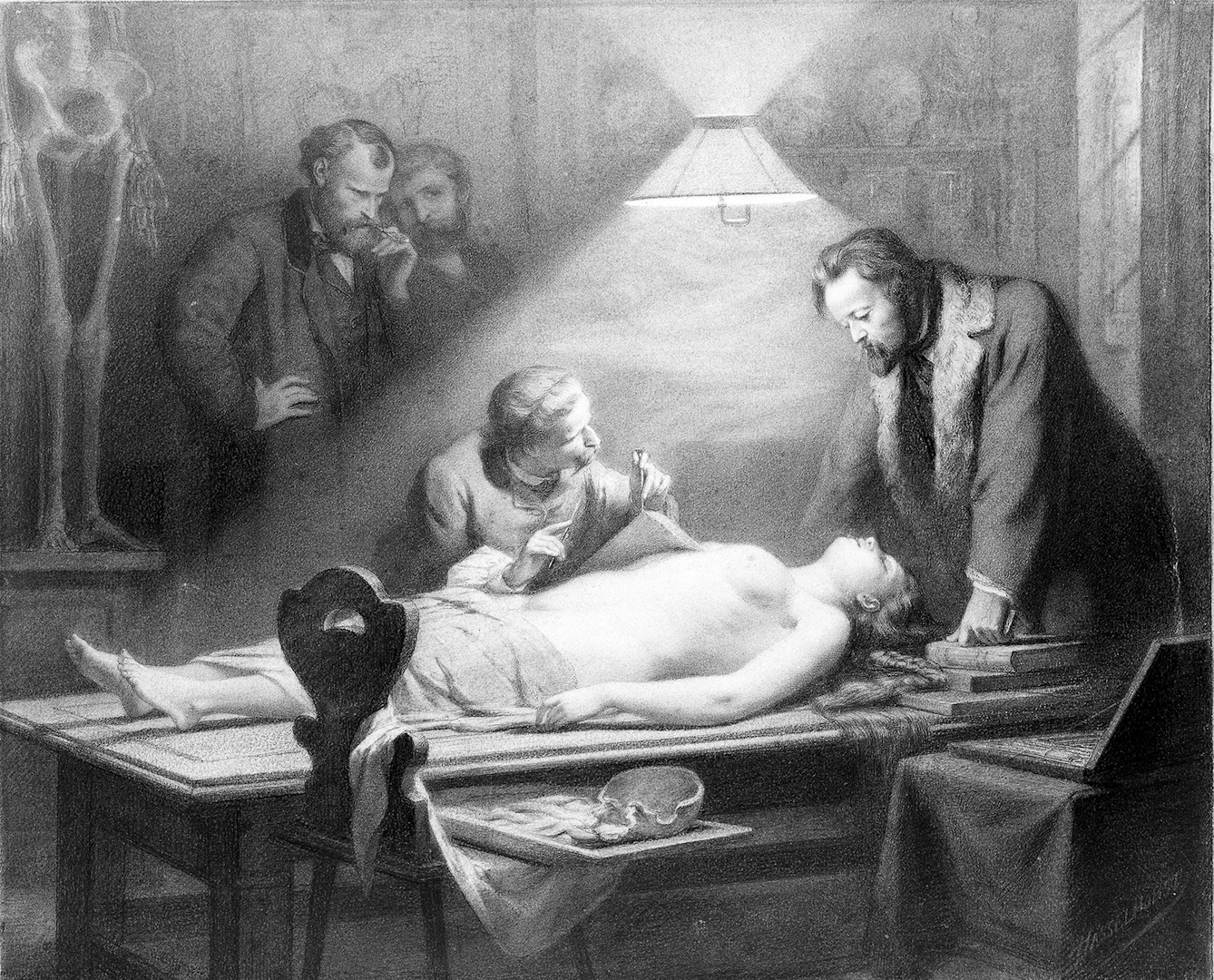

This 1864 chalk drawing by J. H. Hasselhorst shows a dissection directed by J. Ch. G. Lucae (1814-1885) in order to determine the ideal female proportions.

It's 15 years since the last public dissection of a human body took place in England, performed by Gunther Von Hagens in November 2002. Gunther wanted to demystify the post-mortem examination, but was warned by the British government that he could be conducting a criminal act. The dissection went ahead in front of an audience of 500 people, and was even broadcast on Channel 4. Before this, the last time a dissection took place in public was 1832. It was around this time that William Burke and William Hare were arrested for murdering 16 people for the purpose of dissection. The resulting outcry led to the 1832 Anatomy Act, which ended the use of public dissection as punishment, only to put the onus of medical research onto the poor. Those who had no family, or who were vulnerable, impoverished or mentally ill, could legally be obtained for dissection after their death.

Post-mortems are today perhaps most closely connected with forensics. Dr Bernard Spilsbury (1877–1947) gained fame and notoriety by testifying in a number of contentious murder cases. His career in forensic medicine began in London in 1905 when he was appointed by St Mary’s Hospital to conduct post-mortem examinations for all of the hospital’s cases of sudden death. Conducting such examinations became Spilsbury’s special expertise and by the end of his 40-year career he had carried out an estimated 20,000 autopsies.

In pictures

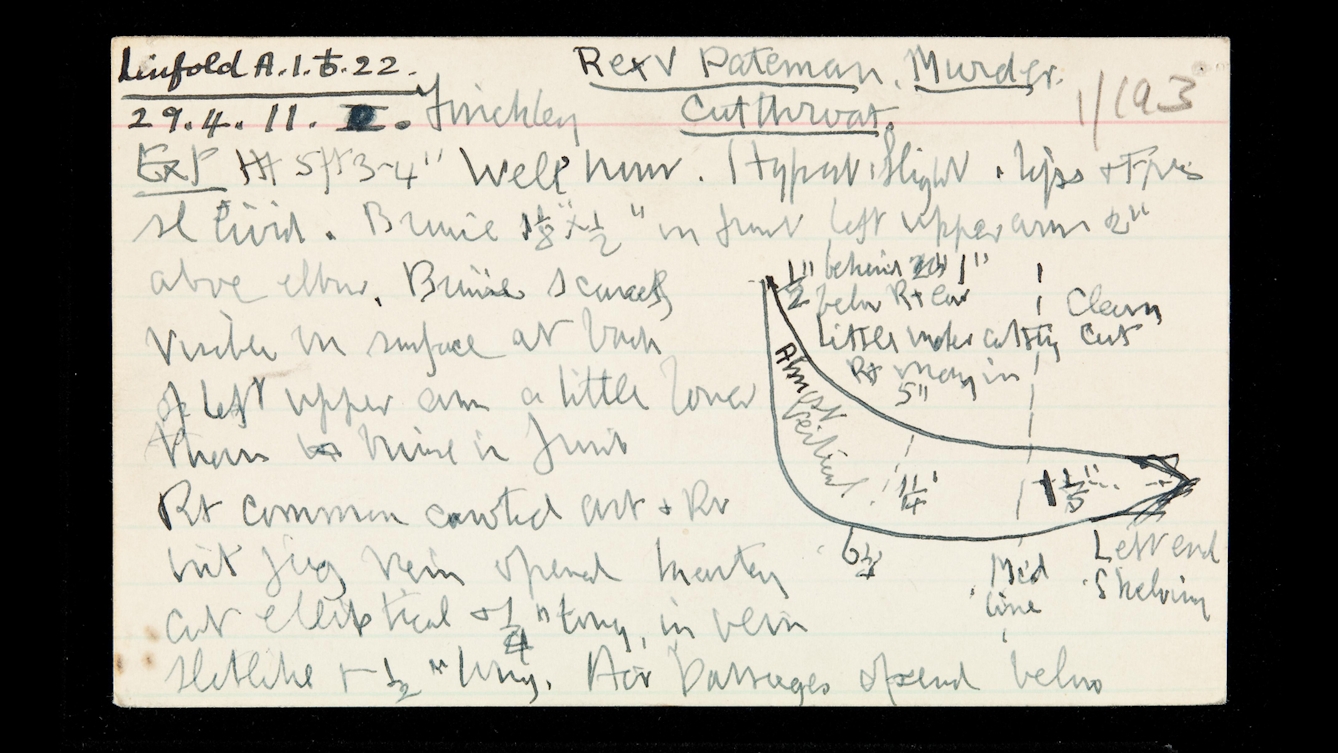

One of Dr Bernard Spilsbury's case cards, here describing murder by cutting of the throat.

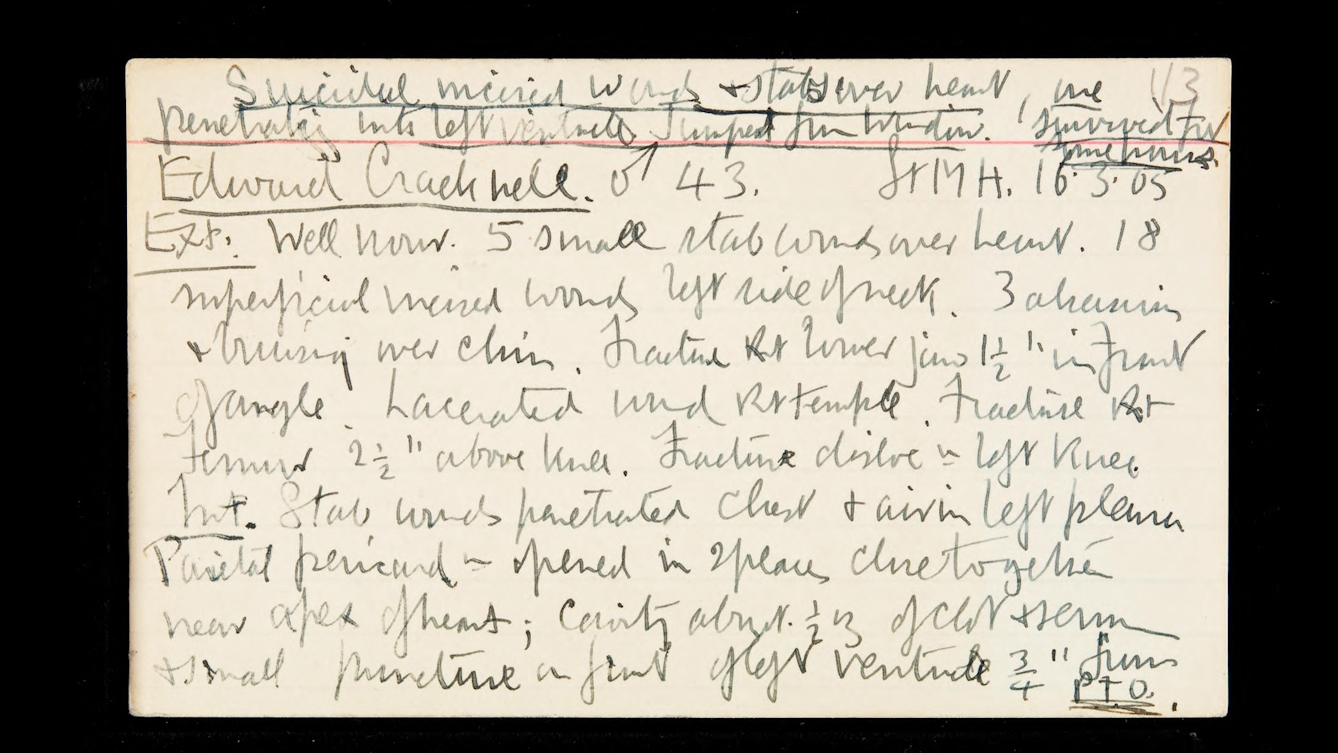

One of Dr Bernard Spilsbury's case cards, here describing suicide by stabbing and jumping from a window.

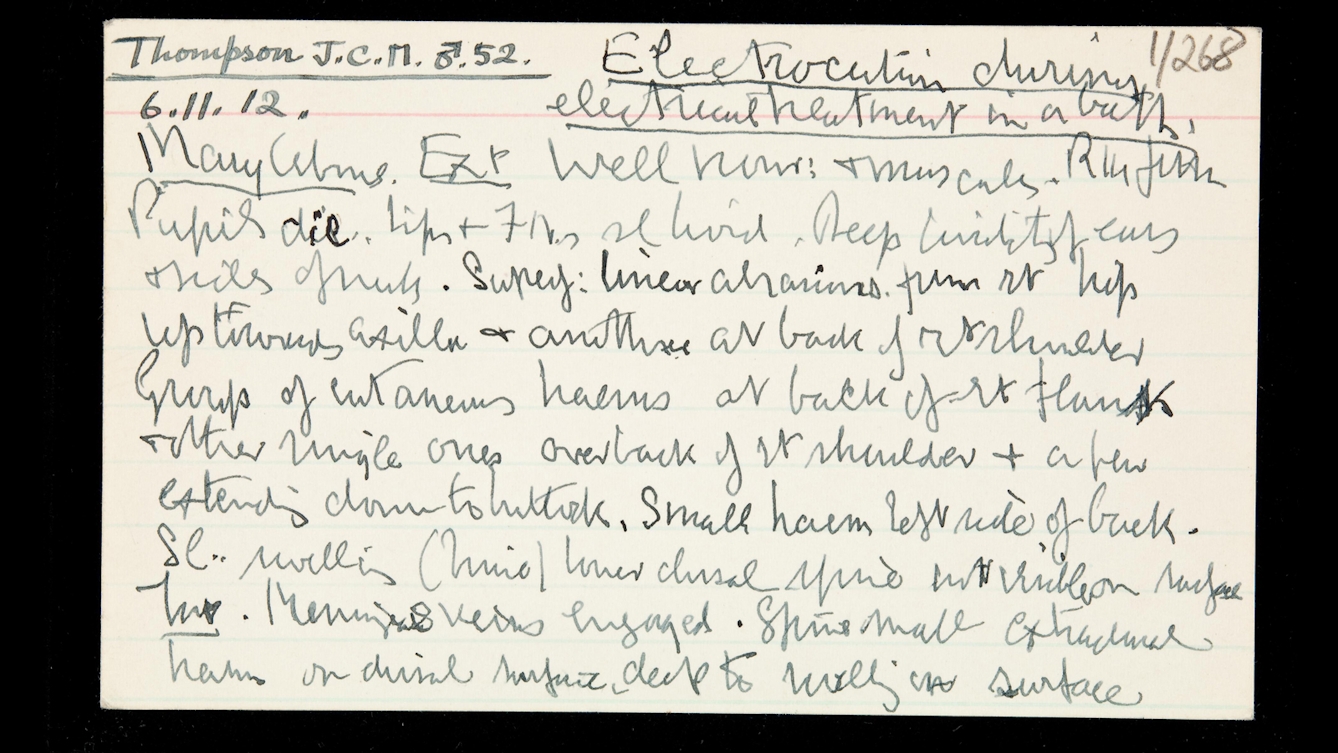

One of Dr Bernard Spilsbury's case cards, here describing someone electrocuted during treatment for arthritis.

Considered by many as the father of modern forensic pathology, Spilsbury’s work was crucial in establishing the importance of precise post-mortem examinations for the conviction of criminals. He kept personal records of the pathological investigations he conducted, collated on over 7,000 index cards. These are held in the Wellcome Library archives, and feature on the Wellcome Collection website.

Outside of these kinds of investigations, where the cause of death needs to be explained, today all bodies dissected in the UK have been donated by the owners themselves, a situation that doctors and students feel is more ethical and respectful. This was made possible by the Anatomy Act 1984, which simplified donation, and the Human Tissue Act 2004, which further regulated it. It’s also possible to digitise human cadavers in order to create virtual dissections that can be used repeatedly, such as the Visible Human Project. Legalising voluntary human body donation, and divorcing it from punishment and poverty, has humanised the scientific use of human cadavers.

About the contributors

Taryn Cain

Taryn Cain is a Visitor Experience Assistant at Wellcome Collection.